Let’s begin with our education system. When a student successfully completes their Ordinary Levels (O/Ls), they are segregated into the streams of commerce, arts, and those with the best results choose either maths or bioscience. They embark in a completely new direction from the humble times of O/Ls. A student, at the end of their studies in their chosen field, can become a medical practitioner, legal professional, or even an engineer.

Let’s begin with our education system. When a student successfully completes their Ordinary Levels (O/Ls), they are segregated into the streams of commerce, arts, and those with the best results choose either maths or bioscience. They embark in a completely new direction from the humble times of O/Ls. A student, at the end of their studies in their chosen field, can become a medical practitioner, legal professional, or even an engineer.

However, during their time at university, or as a matter of fact even in school, their basic knowledge in economics, i.e. what drives inflation, what determines interest rates, and why they are receiving less dollars than last year at the money changer, is at the mercy of a silver-tongued politician, a master in the art of selling excuses; excuses which are hastily gulped by you, the ordinary citizen.

The current economic situation created by Covid-19 is a sterling example of this disconnect. Many well-educated citizens who haven’t studied rudimentary economics during their learning years join the workforce in obedience. What you don’t know won’t hurt you. Sometimes, even those who studied economics have forgotten that economics is the social science of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. We all often fail to possess the common sense that dictates we have to make a continuous effort when making our choices with the availability of limited resources, and organise and co-ordinate to achieve maximum output by increasing productivity.

Ultimately, economics is about you.

In this context, the “ability to test” at present is our most limited and most scarce resource. How we utilise it to the greatest degree is probably the decision-maker of how fast we can overcome and minimise its impact on the wallet of each Sri Lankan.

Testing in isolation will not work without the policies of social distancing and medical policy management. Economics, medicine, bioscience, technology; anything for that matter, is no longer isolated. There is always an economic angle, and we have to find the winning formula to come out of Covid-19.

Testing strategy

The countries that faced the pandemic successfully have one thing in common – their testing strategy and co-ordination between policies has been incredible.

New Zealand, Vietnam, South Korea, the unsung hero Taiwan, and even China have given absolute priority to testing. The ability to test has been discussed on various platforms in Sri Lanka. But still, the public seems to possess an attitude where they feel “this too shall pass”.

[caption id="attachment_82809" align="alignleft" width="287"]

Many well-educated citizens who haven’t studied rudimentary economics during their learning years join the workforce in obedience. What you don’t know won’t hurt you. Sometimes, even those who studied economics have forgotten that economics is the social science of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. We all often fail to possess the common sense that dictates we have to make a continuous effort when making our choices with the availability of limited resources, and organise and co-ordinate to achieve maximum output by increasing productivity.

Ultimately, economics is about you.

In this context, the “ability to test” at present is our most limited and most scarce resource. How we utilise it to the greatest degree is probably the decision-maker of how fast we can overcome and minimise its impact on the wallet of each Sri Lankan.

Testing in isolation will not work without the policies of social distancing and medical policy management. Economics, medicine, bioscience, technology; anything for that matter, is no longer isolated. There is always an economic angle, and we have to find the winning formula to come out of Covid-19.

Testing strategy

The countries that faced the pandemic successfully have one thing in common – their testing strategy and co-ordination between policies has been incredible.

New Zealand, Vietnam, South Korea, the unsung hero Taiwan, and even China have given absolute priority to testing. The ability to test has been discussed on various platforms in Sri Lanka. But still, the public seems to possess an attitude where they feel “this too shall pass”.

[caption id="attachment_82809" align="alignleft" width="287"] Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (Accessed on 1 May 2020)[/caption]

Some tend to think opening up would mark the end of the battle, without weighing the pros and cons to the economy. Let’s face the grim reality. We are not a rich country and the world doesn’t demand our currency. Therefore, excessive money printing is not a solution and is in fact the opposite of a solution.

Hence, the only viable economic option is to be at the helm of the new normal, and “testing” will determine the nature of the new normal.

Sri Lanka did a commendable job in combating Wave 1. (Wave 1 refers to infected cases directly from China). We had a very successful quarantine process and all cases were indexed (the infected person was traceable) at the beginning and were identified, and we did not provide any space for progression to community transmission (infected cases forming small clusters of the population). In contrast, some developed countries like Italy and the US were hit immediately with community transmission right from Wave 1.

However, Sri Lanka has seen a sudden uptick in cases as a result of co-ordination issues between our social distancing policy and a few vital loopholes in our testing policy.

At the beginning, the testing capacity was about 100 and we took a considerable amount of time to increase that limit to 1,000. Testing even at this juncture is a limited resource, so we have to maximise productivity on testing. We have to maximise resources to increase testing capacity, while also ensuring that we test the right samples while the overall testing numbers are increased. That is where exactly we slipped up (Advocata has already highlighted this loophole in testing policy in our publications).

We took a fairly long time to increase testing and it is yet not up to a reasonable level. We did not utilise the private sector from the get-go, even though it has critical capacity for lab tests in the island.

Additional lapses in testing the forces, who are a high-risk segment (as they manage the isolation on the frontlines), caused a sudden increase in infections.

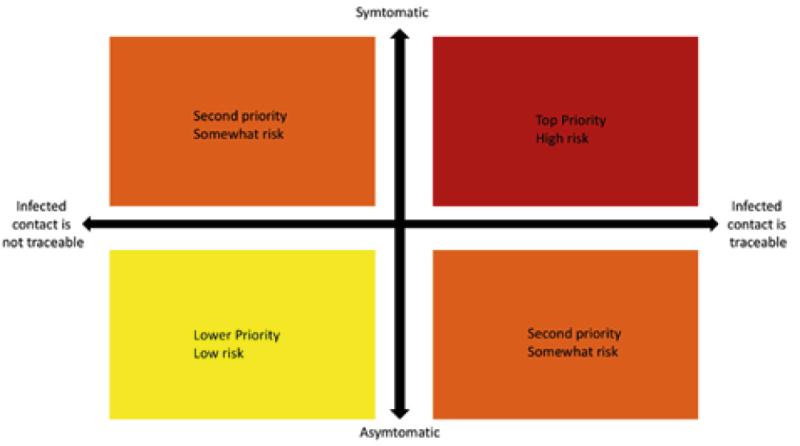

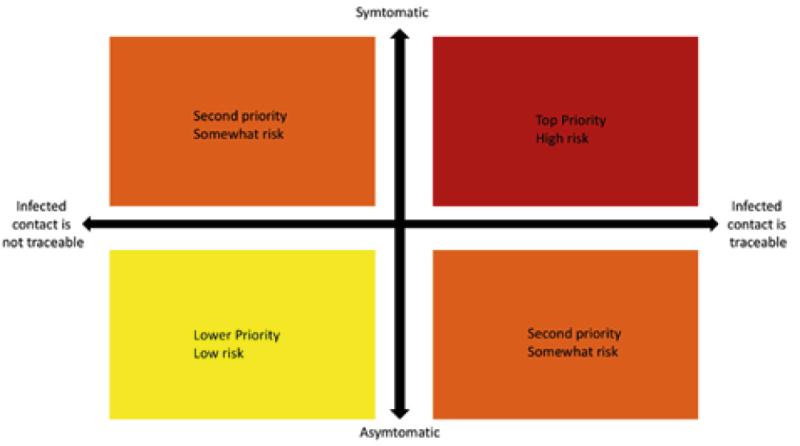

According to medical experts’ opinions, some Covid-19-infected cases indicate symptoms (symptomatic cases) while there are many that don’t indicate symptoms (asymptotic cases). However, they both are the carriers of the virus.

Since our testing capacity is limited, our testing strategy has to prioritise individuals who are symptomatic and who have been in contact with a previously identified patient. In economic terms, we have the opportunity cost of not testing asymptomatic cases at the beginning. But it isn’t that simple; there are some high-risk groups who arrived from overseas and some asymptomatic cases were also in quarantine centres. So, maximising the limited resource “testing” became very complicated.

We did not expect a member in the tri-forces to get infected, and evaluate the possibility of them carrying the virus across domestic borders as a result of their high-frequency commutes. Some of them, having gone on leave to take a break after performing yeoman service, have now become part of the problem by increasing the probability of more cases in low-risk areas.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="422"]

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (Accessed on 1 May 2020)[/caption]

Some tend to think opening up would mark the end of the battle, without weighing the pros and cons to the economy. Let’s face the grim reality. We are not a rich country and the world doesn’t demand our currency. Therefore, excessive money printing is not a solution and is in fact the opposite of a solution.

Hence, the only viable economic option is to be at the helm of the new normal, and “testing” will determine the nature of the new normal.

Sri Lanka did a commendable job in combating Wave 1. (Wave 1 refers to infected cases directly from China). We had a very successful quarantine process and all cases were indexed (the infected person was traceable) at the beginning and were identified, and we did not provide any space for progression to community transmission (infected cases forming small clusters of the population). In contrast, some developed countries like Italy and the US were hit immediately with community transmission right from Wave 1.

However, Sri Lanka has seen a sudden uptick in cases as a result of co-ordination issues between our social distancing policy and a few vital loopholes in our testing policy.

At the beginning, the testing capacity was about 100 and we took a considerable amount of time to increase that limit to 1,000. Testing even at this juncture is a limited resource, so we have to maximise productivity on testing. We have to maximise resources to increase testing capacity, while also ensuring that we test the right samples while the overall testing numbers are increased. That is where exactly we slipped up (Advocata has already highlighted this loophole in testing policy in our publications).

We took a fairly long time to increase testing and it is yet not up to a reasonable level. We did not utilise the private sector from the get-go, even though it has critical capacity for lab tests in the island.

Additional lapses in testing the forces, who are a high-risk segment (as they manage the isolation on the frontlines), caused a sudden increase in infections.

According to medical experts’ opinions, some Covid-19-infected cases indicate symptoms (symptomatic cases) while there are many that don’t indicate symptoms (asymptotic cases). However, they both are the carriers of the virus.

Since our testing capacity is limited, our testing strategy has to prioritise individuals who are symptomatic and who have been in contact with a previously identified patient. In economic terms, we have the opportunity cost of not testing asymptomatic cases at the beginning. But it isn’t that simple; there are some high-risk groups who arrived from overseas and some asymptomatic cases were also in quarantine centres. So, maximising the limited resource “testing” became very complicated.

We did not expect a member in the tri-forces to get infected, and evaluate the possibility of them carrying the virus across domestic borders as a result of their high-frequency commutes. Some of them, having gone on leave to take a break after performing yeoman service, have now become part of the problem by increasing the probability of more cases in low-risk areas.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="422"] Basic visual diagram to understand the initial testing strategy[/caption]

Countries like Vietnam identified this loophole early and conducted frequent tests among high-risk groups. Drivers, cleaning staff at hospitals, and all individuals commuting often too fell into high-risk categories.

Increasing testing capacity

One main reason for the delay in increasing testing capacity was not seeking to engage the private sector in testing at the beginning of the pandemic. Private sector labs are mainly run by major hospital groups that are well regulated by the Ministry of Health and have the critical capacity to get the numbers in.

A PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test is a confirmatory test (i.e. symptoms have to be indicated and a doctor has to recommend the test). An individual cannot get it done as a screening test (a test to identify an infection/disease). As a result, private hospitals are allowed to conduct PCR tests for in-house patients only.

Of course, the cost of testing in the private sector would be higher, but restricting the private sector from conducting the tests as a laboratory test and imposing price controls on the tests, were a surefire way of discouraging volunteer testing.

The outcome would be that someone who could afford a test at a higher price is forced to utilise the state health apparatus, adding further strain on limited resources.

At the same time, price controls discourage the private sector to invest and further expand testing capacity. In an ideal scenario, the private sector has to be encouraged to conduct the tests out of the hospital premises to reduce the degree of transmission of the disease.

Given that new infections are now being reported in clusters, we can’t adhere to our previous testing priority strategy, as now asymptotic cases are being reported and the opportunity of voluntary testing has to be opened up. The cost of an idle economy is unbearable for a developing country like Sri Lanka.

Solution

The only solution lies in improving our testing strategy and increasing capacity. It was reported that some PCR tests were locally made, which is commendable and we should encourage them to upscale it to a commercial level.

Basic visual diagram to understand the initial testing strategy[/caption]

Countries like Vietnam identified this loophole early and conducted frequent tests among high-risk groups. Drivers, cleaning staff at hospitals, and all individuals commuting often too fell into high-risk categories.

Increasing testing capacity

One main reason for the delay in increasing testing capacity was not seeking to engage the private sector in testing at the beginning of the pandemic. Private sector labs are mainly run by major hospital groups that are well regulated by the Ministry of Health and have the critical capacity to get the numbers in.

A PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test is a confirmatory test (i.e. symptoms have to be indicated and a doctor has to recommend the test). An individual cannot get it done as a screening test (a test to identify an infection/disease). As a result, private hospitals are allowed to conduct PCR tests for in-house patients only.

Of course, the cost of testing in the private sector would be higher, but restricting the private sector from conducting the tests as a laboratory test and imposing price controls on the tests, were a surefire way of discouraging volunteer testing.

The outcome would be that someone who could afford a test at a higher price is forced to utilise the state health apparatus, adding further strain on limited resources.

At the same time, price controls discourage the private sector to invest and further expand testing capacity. In an ideal scenario, the private sector has to be encouraged to conduct the tests out of the hospital premises to reduce the degree of transmission of the disease.

Given that new infections are now being reported in clusters, we can’t adhere to our previous testing priority strategy, as now asymptotic cases are being reported and the opportunity of voluntary testing has to be opened up. The cost of an idle economy is unbearable for a developing country like Sri Lanka.

Solution

The only solution lies in improving our testing strategy and increasing capacity. It was reported that some PCR tests were locally made, which is commendable and we should encourage them to upscale it to a commercial level.

However, we must bear in mind that introducing commercial-scale medical equipment takes time as the process needs extensive testing in order to get the relevant approvals to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Increasing testing by using basic economics by considering what is available is a more feasible option.

Having fewer regulations in the private sector on testing, while the Government continues to provide free testing is the most economically feasible option. Engaging the private sector will save the government sector the opportunity cost of testing more cases who can’t afford to pay for it.

As community-level infections have been reported now, a voluntary testing ability is a must.

Only the private sector is likely to bring the investment for advanced and convenient testing such as drive-through tests and mass-scale testing needed for industries.

We need to learn to co-exist with Covid-19 till the boffins at the labs come up with a vaccine, which is still in the distant horizon. Hence, at the moment, increasing the number of tests conducted is the only way to defeat the invisible enemy.

(The writer is the Chief Operating Officer of the Advocata Institute and can be contacted at dhananath@advocata.org. Learn more about Advocata’s work at www.advocata.org. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, or anyone affiliated with the institute)

However, we must bear in mind that introducing commercial-scale medical equipment takes time as the process needs extensive testing in order to get the relevant approvals to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Increasing testing by using basic economics by considering what is available is a more feasible option.

Having fewer regulations in the private sector on testing, while the Government continues to provide free testing is the most economically feasible option. Engaging the private sector will save the government sector the opportunity cost of testing more cases who can’t afford to pay for it.

As community-level infections have been reported now, a voluntary testing ability is a must.

Only the private sector is likely to bring the investment for advanced and convenient testing such as drive-through tests and mass-scale testing needed for industries.

We need to learn to co-exist with Covid-19 till the boffins at the labs come up with a vaccine, which is still in the distant horizon. Hence, at the moment, increasing the number of tests conducted is the only way to defeat the invisible enemy.

(The writer is the Chief Operating Officer of the Advocata Institute and can be contacted at dhananath@advocata.org. Learn more about Advocata’s work at www.advocata.org. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, or anyone affiliated with the institute)

Many well-educated citizens who haven’t studied rudimentary economics during their learning years join the workforce in obedience. What you don’t know won’t hurt you. Sometimes, even those who studied economics have forgotten that economics is the social science of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. We all often fail to possess the common sense that dictates we have to make a continuous effort when making our choices with the availability of limited resources, and organise and co-ordinate to achieve maximum output by increasing productivity.

Ultimately, economics is about you.

In this context, the “ability to test” at present is our most limited and most scarce resource. How we utilise it to the greatest degree is probably the decision-maker of how fast we can overcome and minimise its impact on the wallet of each Sri Lankan.

Testing in isolation will not work without the policies of social distancing and medical policy management. Economics, medicine, bioscience, technology; anything for that matter, is no longer isolated. There is always an economic angle, and we have to find the winning formula to come out of Covid-19.

Testing strategy

The countries that faced the pandemic successfully have one thing in common – their testing strategy and co-ordination between policies has been incredible.

New Zealand, Vietnam, South Korea, the unsung hero Taiwan, and even China have given absolute priority to testing. The ability to test has been discussed on various platforms in Sri Lanka. But still, the public seems to possess an attitude where they feel “this too shall pass”.

[caption id="attachment_82809" align="alignleft" width="287"]

Many well-educated citizens who haven’t studied rudimentary economics during their learning years join the workforce in obedience. What you don’t know won’t hurt you. Sometimes, even those who studied economics have forgotten that economics is the social science of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. We all often fail to possess the common sense that dictates we have to make a continuous effort when making our choices with the availability of limited resources, and organise and co-ordinate to achieve maximum output by increasing productivity.

Ultimately, economics is about you.

In this context, the “ability to test” at present is our most limited and most scarce resource. How we utilise it to the greatest degree is probably the decision-maker of how fast we can overcome and minimise its impact on the wallet of each Sri Lankan.

Testing in isolation will not work without the policies of social distancing and medical policy management. Economics, medicine, bioscience, technology; anything for that matter, is no longer isolated. There is always an economic angle, and we have to find the winning formula to come out of Covid-19.

Testing strategy

The countries that faced the pandemic successfully have one thing in common – their testing strategy and co-ordination between policies has been incredible.

New Zealand, Vietnam, South Korea, the unsung hero Taiwan, and even China have given absolute priority to testing. The ability to test has been discussed on various platforms in Sri Lanka. But still, the public seems to possess an attitude where they feel “this too shall pass”.

[caption id="attachment_82809" align="alignleft" width="287"] Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (Accessed on 1 May 2020)[/caption]

Some tend to think opening up would mark the end of the battle, without weighing the pros and cons to the economy. Let’s face the grim reality. We are not a rich country and the world doesn’t demand our currency. Therefore, excessive money printing is not a solution and is in fact the opposite of a solution.

Hence, the only viable economic option is to be at the helm of the new normal, and “testing” will determine the nature of the new normal.

Sri Lanka did a commendable job in combating Wave 1. (Wave 1 refers to infected cases directly from China). We had a very successful quarantine process and all cases were indexed (the infected person was traceable) at the beginning and were identified, and we did not provide any space for progression to community transmission (infected cases forming small clusters of the population). In contrast, some developed countries like Italy and the US were hit immediately with community transmission right from Wave 1.

However, Sri Lanka has seen a sudden uptick in cases as a result of co-ordination issues between our social distancing policy and a few vital loopholes in our testing policy.

At the beginning, the testing capacity was about 100 and we took a considerable amount of time to increase that limit to 1,000. Testing even at this juncture is a limited resource, so we have to maximise productivity on testing. We have to maximise resources to increase testing capacity, while also ensuring that we test the right samples while the overall testing numbers are increased. That is where exactly we slipped up (Advocata has already highlighted this loophole in testing policy in our publications).

We took a fairly long time to increase testing and it is yet not up to a reasonable level. We did not utilise the private sector from the get-go, even though it has critical capacity for lab tests in the island.

Additional lapses in testing the forces, who are a high-risk segment (as they manage the isolation on the frontlines), caused a sudden increase in infections.

According to medical experts’ opinions, some Covid-19-infected cases indicate symptoms (symptomatic cases) while there are many that don’t indicate symptoms (asymptotic cases). However, they both are the carriers of the virus.

Since our testing capacity is limited, our testing strategy has to prioritise individuals who are symptomatic and who have been in contact with a previously identified patient. In economic terms, we have the opportunity cost of not testing asymptomatic cases at the beginning. But it isn’t that simple; there are some high-risk groups who arrived from overseas and some asymptomatic cases were also in quarantine centres. So, maximising the limited resource “testing” became very complicated.

We did not expect a member in the tri-forces to get infected, and evaluate the possibility of them carrying the virus across domestic borders as a result of their high-frequency commutes. Some of them, having gone on leave to take a break after performing yeoman service, have now become part of the problem by increasing the probability of more cases in low-risk areas.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="422"]

Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (Accessed on 1 May 2020)[/caption]

Some tend to think opening up would mark the end of the battle, without weighing the pros and cons to the economy. Let’s face the grim reality. We are not a rich country and the world doesn’t demand our currency. Therefore, excessive money printing is not a solution and is in fact the opposite of a solution.

Hence, the only viable economic option is to be at the helm of the new normal, and “testing” will determine the nature of the new normal.

Sri Lanka did a commendable job in combating Wave 1. (Wave 1 refers to infected cases directly from China). We had a very successful quarantine process and all cases were indexed (the infected person was traceable) at the beginning and were identified, and we did not provide any space for progression to community transmission (infected cases forming small clusters of the population). In contrast, some developed countries like Italy and the US were hit immediately with community transmission right from Wave 1.

However, Sri Lanka has seen a sudden uptick in cases as a result of co-ordination issues between our social distancing policy and a few vital loopholes in our testing policy.

At the beginning, the testing capacity was about 100 and we took a considerable amount of time to increase that limit to 1,000. Testing even at this juncture is a limited resource, so we have to maximise productivity on testing. We have to maximise resources to increase testing capacity, while also ensuring that we test the right samples while the overall testing numbers are increased. That is where exactly we slipped up (Advocata has already highlighted this loophole in testing policy in our publications).

We took a fairly long time to increase testing and it is yet not up to a reasonable level. We did not utilise the private sector from the get-go, even though it has critical capacity for lab tests in the island.

Additional lapses in testing the forces, who are a high-risk segment (as they manage the isolation on the frontlines), caused a sudden increase in infections.

According to medical experts’ opinions, some Covid-19-infected cases indicate symptoms (symptomatic cases) while there are many that don’t indicate symptoms (asymptotic cases). However, they both are the carriers of the virus.

Since our testing capacity is limited, our testing strategy has to prioritise individuals who are symptomatic and who have been in contact with a previously identified patient. In economic terms, we have the opportunity cost of not testing asymptomatic cases at the beginning. But it isn’t that simple; there are some high-risk groups who arrived from overseas and some asymptomatic cases were also in quarantine centres. So, maximising the limited resource “testing” became very complicated.

We did not expect a member in the tri-forces to get infected, and evaluate the possibility of them carrying the virus across domestic borders as a result of their high-frequency commutes. Some of them, having gone on leave to take a break after performing yeoman service, have now become part of the problem by increasing the probability of more cases in low-risk areas.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="422"] Basic visual diagram to understand the initial testing strategy[/caption]

Countries like Vietnam identified this loophole early and conducted frequent tests among high-risk groups. Drivers, cleaning staff at hospitals, and all individuals commuting often too fell into high-risk categories.

Increasing testing capacity

One main reason for the delay in increasing testing capacity was not seeking to engage the private sector in testing at the beginning of the pandemic. Private sector labs are mainly run by major hospital groups that are well regulated by the Ministry of Health and have the critical capacity to get the numbers in.

A PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test is a confirmatory test (i.e. symptoms have to be indicated and a doctor has to recommend the test). An individual cannot get it done as a screening test (a test to identify an infection/disease). As a result, private hospitals are allowed to conduct PCR tests for in-house patients only.

Of course, the cost of testing in the private sector would be higher, but restricting the private sector from conducting the tests as a laboratory test and imposing price controls on the tests, were a surefire way of discouraging volunteer testing.

The outcome would be that someone who could afford a test at a higher price is forced to utilise the state health apparatus, adding further strain on limited resources.

At the same time, price controls discourage the private sector to invest and further expand testing capacity. In an ideal scenario, the private sector has to be encouraged to conduct the tests out of the hospital premises to reduce the degree of transmission of the disease.

Given that new infections are now being reported in clusters, we can’t adhere to our previous testing priority strategy, as now asymptotic cases are being reported and the opportunity of voluntary testing has to be opened up. The cost of an idle economy is unbearable for a developing country like Sri Lanka.

Solution

The only solution lies in improving our testing strategy and increasing capacity. It was reported that some PCR tests were locally made, which is commendable and we should encourage them to upscale it to a commercial level.

Basic visual diagram to understand the initial testing strategy[/caption]

Countries like Vietnam identified this loophole early and conducted frequent tests among high-risk groups. Drivers, cleaning staff at hospitals, and all individuals commuting often too fell into high-risk categories.

Increasing testing capacity

One main reason for the delay in increasing testing capacity was not seeking to engage the private sector in testing at the beginning of the pandemic. Private sector labs are mainly run by major hospital groups that are well regulated by the Ministry of Health and have the critical capacity to get the numbers in.

A PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test is a confirmatory test (i.e. symptoms have to be indicated and a doctor has to recommend the test). An individual cannot get it done as a screening test (a test to identify an infection/disease). As a result, private hospitals are allowed to conduct PCR tests for in-house patients only.

Of course, the cost of testing in the private sector would be higher, but restricting the private sector from conducting the tests as a laboratory test and imposing price controls on the tests, were a surefire way of discouraging volunteer testing.

The outcome would be that someone who could afford a test at a higher price is forced to utilise the state health apparatus, adding further strain on limited resources.

At the same time, price controls discourage the private sector to invest and further expand testing capacity. In an ideal scenario, the private sector has to be encouraged to conduct the tests out of the hospital premises to reduce the degree of transmission of the disease.

Given that new infections are now being reported in clusters, we can’t adhere to our previous testing priority strategy, as now asymptotic cases are being reported and the opportunity of voluntary testing has to be opened up. The cost of an idle economy is unbearable for a developing country like Sri Lanka.

Solution

The only solution lies in improving our testing strategy and increasing capacity. It was reported that some PCR tests were locally made, which is commendable and we should encourage them to upscale it to a commercial level.

However, we must bear in mind that introducing commercial-scale medical equipment takes time as the process needs extensive testing in order to get the relevant approvals to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Increasing testing by using basic economics by considering what is available is a more feasible option.

Having fewer regulations in the private sector on testing, while the Government continues to provide free testing is the most economically feasible option. Engaging the private sector will save the government sector the opportunity cost of testing more cases who can’t afford to pay for it.

As community-level infections have been reported now, a voluntary testing ability is a must.

Only the private sector is likely to bring the investment for advanced and convenient testing such as drive-through tests and mass-scale testing needed for industries.

We need to learn to co-exist with Covid-19 till the boffins at the labs come up with a vaccine, which is still in the distant horizon. Hence, at the moment, increasing the number of tests conducted is the only way to defeat the invisible enemy.

(The writer is the Chief Operating Officer of the Advocata Institute and can be contacted at dhananath@advocata.org. Learn more about Advocata’s work at www.advocata.org. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, or anyone affiliated with the institute)

However, we must bear in mind that introducing commercial-scale medical equipment takes time as the process needs extensive testing in order to get the relevant approvals to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Increasing testing by using basic economics by considering what is available is a more feasible option.

Having fewer regulations in the private sector on testing, while the Government continues to provide free testing is the most economically feasible option. Engaging the private sector will save the government sector the opportunity cost of testing more cases who can’t afford to pay for it.

As community-level infections have been reported now, a voluntary testing ability is a must.

Only the private sector is likely to bring the investment for advanced and convenient testing such as drive-through tests and mass-scale testing needed for industries.

We need to learn to co-exist with Covid-19 till the boffins at the labs come up with a vaccine, which is still in the distant horizon. Hence, at the moment, increasing the number of tests conducted is the only way to defeat the invisible enemy.

(The writer is the Chief Operating Officer of the Advocata Institute and can be contacted at dhananath@advocata.org. Learn more about Advocata’s work at www.advocata.org. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, or anyone affiliated with the institute)