Last week, the Government proposed a ban on sachet packets as a measure to protect the environment. And now, another proposal has been tabled – banning the slaughter of cattle. This is not the first time such strict measures have been imposed by consecutive governments, but it is paramount that we understand the economics and unintended consequences behind “banning”.

Last week, the Government proposed a ban on sachet packets as a measure to protect the environment. And now, another proposal has been tabled – banning the slaughter of cattle. This is not the first time such strict measures have been imposed by consecutive governments, but it is paramount that we understand the economics and unintended consequences behind “banning”.

Before we jump to any conclusions, let’s just take a look at the results of similar policies adopted in the past, to get a taste of this “banning strategy”.

Previously, we saw a proposal to ban polythene below 20 microns in thickness to protect the environment (1) and it was not too long ago when the former President announced a ban on chainsaws and carpentry sheds (2). A simple visit to the market is sufficient to demonstrate the extent these banning mechanisms have been productive.

Earlier this year, the Government learned a bitter lesson on imposing “price controls” (which is sort of a ban on selling at high prices) on tin fish and dhal. The price controls had to be revoked due to obvious market disruptions. Prices shot up, and there were shortages in the market, which was the complete opposite of what the Government intended.

A common belief is that the “banning strategy” often fails or is less effective due to poor implementation. This is far from the truth. There is very much a market and an economic dimension that show the concept in itself is flawed, which we often fail to understand.

Emotional policymakers often get the art of public policy drastically wrong. They view it through an accounting lens due to a lack of knowledge on human behavioural economics and the presence of the concept called “markets”. As a result, all good intentions result in far worse consequences.

Ban on sachets

The concept of sachets was introduced by FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) market players on the basis of affordability and as a measure of resource allocation. Someone who cannot afford a full bottle of shampoo or any other equivalent product can use a sachet as a one-time useable product, based on the requirement. This is easy on customers’ wallets and provides value for money.

A good reason why sachets are predominantly available in general trade and mom-and-pop shops as opposed to modern trade is its easy access and affordability for the poor. On the other hand, from the manufacturer’s end, sachets help to allocate raw materials effectively and allow them to reach the market.

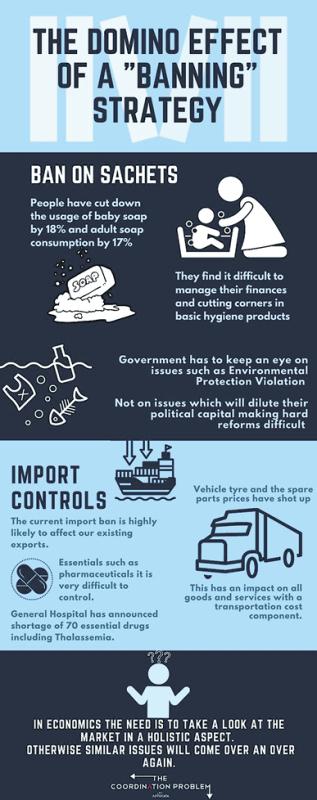

According to a recent article by Dr. Rohantha Athukorala (3), a Neilson Survey revealed that people have reduced the usage of baby soap by 18% and adult soap consumption by 17%. This indicates how people who find it difficult to manage their finances resort to eliminating basic hygiene products like adult and baby soap due to unaffordability. Cutting down on baby soap indicates a booming cost of living problem which goes beyond soap usage.

The ban on sachets will be a double whammy for most vulnerable people in society who are voiceless. All FMCG companies spend an enormous amount of money before they launch any SKU (stock-keeping unit), and we need to understand this was a market demand.

A common belief is that the “banning strategy” often fails or is less effective due to poor implementation. This is far from the truth. There is very much a market and an economic dimension that show the concept in itself is flawed, which we often fail to understand.

Emotional policymakers often get the art of public policy drastically wrong. They view it through an accounting lens due to a lack of knowledge on human behavioural economics and the presence of the concept called “markets”. As a result, all good intentions result in far worse consequences.

Ban on sachets

The concept of sachets was introduced by FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) market players on the basis of affordability and as a measure of resource allocation. Someone who cannot afford a full bottle of shampoo or any other equivalent product can use a sachet as a one-time useable product, based on the requirement. This is easy on customers’ wallets and provides value for money.

A good reason why sachets are predominantly available in general trade and mom-and-pop shops as opposed to modern trade is its easy access and affordability for the poor. On the other hand, from the manufacturer’s end, sachets help to allocate raw materials effectively and allow them to reach the market.

According to a recent article by Dr. Rohantha Athukorala (3), a Neilson Survey revealed that people have reduced the usage of baby soap by 18% and adult soap consumption by 17%. This indicates how people who find it difficult to manage their finances resort to eliminating basic hygiene products like adult and baby soap due to unaffordability. Cutting down on baby soap indicates a booming cost of living problem which goes beyond soap usage.

The ban on sachets will be a double whammy for most vulnerable people in society who are voiceless. All FMCG companies spend an enormous amount of money before they launch any SKU (stock-keeping unit), and we need to understand this was a market demand.

A sudden decision without prior engagement with the industry and relevant stakeholders will push manufactures to an extremely difficult situation, which will demand them to realign their manufacturing and marketing strategies in an already challenged Covid-19 economic environment. We have often forgotten that polythene is a wonderful innovation, and where its hydrocarbons are recycled to produce electronic chips and fabric.

MAS Holdings manufactured a special fabric for our cricket World Cup team with marine plastic waste which received global recognition. This can be utilised as an effective example to understand that the prime need is for setting up proper recycling methods coupled with incentives and disincentives.

Already, the discussion is heated on serious environmental concerns such as that of the Anawilundawa Wetland Sanctuary and many other places across the island, as highlighted through this column last week. The Government has to keep an eye on more macro issues pertaining to environmental protection rather than obsessively focusing on micro issues. These “banning strategies” will dilute the Government’s well-earned political capital, which will make hard reforms difficult in the coming years.

Import controls

Import controls are another form of ban on a temporary basis. The Government’s urgent need to manage its Balance of Payment (BoP) crisis is understandable. However, this requires a series of different actions coupled with temporary solutions such as bailout programmes from the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and clear policy decisions to help make our exports competitive.

Import controls hurt exports as the prices of import substitutes rise, especially where the goods are used as an input for the production of exports. In addition, import substitutes become more profitable to produce than exports.

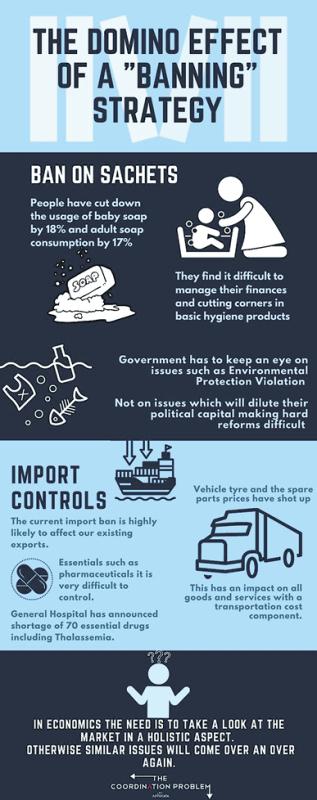

The result of the current import ban is highly likely to affect our existing exports, as we have indicated in this column multiple times. Already, people are struggling to buy phone chargers, repair washing machines, and purchase goods which are required on a daily basis. We are running on existing stocks which will expire soon and prices have already started going up.

On the other hand, in our import bill, the big-ticket item is fuel and essentials such as pharmaceuticals, which are very difficult to control. The General Hospital has already announced a shortage of 70 essential drugs. These drugs are used to treat diseases such as Thalassemia and heart-related conditions (4).

However, trying to cut corners of other imports carry the potential to distort various other markets, businesses, and value chains horizontally, vertically, upstream, and downstream due to price hikes.

Prices of vehicle tyres and spare parts have shot up, which will have an impact on all goods and services with a transportation cost component. At one point, the collective effect of the rising cost of multiple consumable goods and intermediary goods may go beyond people’s affordability.

Releasing import controls at this point would be too late, given the situation of our currency. The higher cost of living will impact labour prices and most of our value addition in exports which are in the form of labour will be uncompetitive over a period, which will affect our main exports such as apparels, tea, and rubber products. In economics, the need is to take a look at the market from a holistic perspective. Otherwise, similar issues will arise over and over again.

The best example is higher prices requested by the poultry industry and the bakery industry. Sri Lanka’s maize production is not at all sufficient for domestic consumption, which is the main source of food for poultry. As a result of higher prices of maize, the prices of poultry products have shot up, which will have an impact on the bakery industry. Now you have a happy maize farmer but an unhappy poultry farmer and a baker. Eventually, this will translate to an unhappy consumer and a very unhappy voter.

A sudden decision without prior engagement with the industry and relevant stakeholders will push manufactures to an extremely difficult situation, which will demand them to realign their manufacturing and marketing strategies in an already challenged Covid-19 economic environment. We have often forgotten that polythene is a wonderful innovation, and where its hydrocarbons are recycled to produce electronic chips and fabric.

MAS Holdings manufactured a special fabric for our cricket World Cup team with marine plastic waste which received global recognition. This can be utilised as an effective example to understand that the prime need is for setting up proper recycling methods coupled with incentives and disincentives.

Already, the discussion is heated on serious environmental concerns such as that of the Anawilundawa Wetland Sanctuary and many other places across the island, as highlighted through this column last week. The Government has to keep an eye on more macro issues pertaining to environmental protection rather than obsessively focusing on micro issues. These “banning strategies” will dilute the Government’s well-earned political capital, which will make hard reforms difficult in the coming years.

Import controls

Import controls are another form of ban on a temporary basis. The Government’s urgent need to manage its Balance of Payment (BoP) crisis is understandable. However, this requires a series of different actions coupled with temporary solutions such as bailout programmes from the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and clear policy decisions to help make our exports competitive.

Import controls hurt exports as the prices of import substitutes rise, especially where the goods are used as an input for the production of exports. In addition, import substitutes become more profitable to produce than exports.

The result of the current import ban is highly likely to affect our existing exports, as we have indicated in this column multiple times. Already, people are struggling to buy phone chargers, repair washing machines, and purchase goods which are required on a daily basis. We are running on existing stocks which will expire soon and prices have already started going up.

On the other hand, in our import bill, the big-ticket item is fuel and essentials such as pharmaceuticals, which are very difficult to control. The General Hospital has already announced a shortage of 70 essential drugs. These drugs are used to treat diseases such as Thalassemia and heart-related conditions (4).

However, trying to cut corners of other imports carry the potential to distort various other markets, businesses, and value chains horizontally, vertically, upstream, and downstream due to price hikes.

Prices of vehicle tyres and spare parts have shot up, which will have an impact on all goods and services with a transportation cost component. At one point, the collective effect of the rising cost of multiple consumable goods and intermediary goods may go beyond people’s affordability.

Releasing import controls at this point would be too late, given the situation of our currency. The higher cost of living will impact labour prices and most of our value addition in exports which are in the form of labour will be uncompetitive over a period, which will affect our main exports such as apparels, tea, and rubber products. In economics, the need is to take a look at the market from a holistic perspective. Otherwise, similar issues will arise over and over again.

The best example is higher prices requested by the poultry industry and the bakery industry. Sri Lanka’s maize production is not at all sufficient for domestic consumption, which is the main source of food for poultry. As a result of higher prices of maize, the prices of poultry products have shot up, which will have an impact on the bakery industry. Now you have a happy maize farmer but an unhappy poultry farmer and a baker. Eventually, this will translate to an unhappy consumer and a very unhappy voter.

Ban on slaughtering cattle

Adding to the banning spree, the proposed ban on slaughtering cattle is the latest. This may cause more damage rather than being helpful for the protection of cattle in Sri Lanka. However, the Cabinet Spokesperson mentioned the proposal was postponed by one month so as to allow for discussions with the relevant stakeholders.

Though the proposal may have been put forward with good intentions in terms of animal cruelty, India is a good example of how such policies don’t work. Cattle owners in India are left with no option other than to resort to the creation of illegal and unsanitary slaughtering houses and illegal markets.

Keeping aside the logical fallacy of placing a ban only on the slaughter of cattle and not the entirety of the poultry and meat industry, and the justification of leaving domestic demand to only be met through the importation of beef, the matter goes far beyond that.

The beef industry does not exist in isolation; our leather industry, dairy industry, and leather exports are also dependent on it. According to the Export Development Board (EDB), in 2016, about 1% of total merchandise exports (5) consisted of footwear and leather products, which has now dropped to 0.6% of our merchandise exports.

According to the EDB, there are about five large companies, 10 medium-scale companies, and more than 1,000 small enterprises and seven tanneries that produce 25 tonnes of leather every day (6).

If passed by Parliament, this proposed ban on cattle slaughter will prevail at the expense of 1,000 small enterprises and exports worth $ 550 million (7). While animal cruelty is of grave importance, sometimes in life we have to keep some markets for the greater good and to avoid much greater negative impacts.

References:

(1) http://www.colombopage.com/archive_17B/Sep01_1504285020CH.php

(2) http://www.adaderana.lk/news/55586/i-will-ban-carpentry-sheds-sawmill-owners-have-5-years-to-find-another-job-president

(3) http://www.ft.lk/columns/Economic-terrorism-by-COVID-19/4-705859

(4) https://mawbima.lk/news search/%20%E0%B6%BB%E0%B6%A2%E0%B6%BA%E0%B7%9A%20%E0%B6%BB%E0%B7%9D%E0%B7%84%E0%B6%BD%E0%B7%8A%20/print-more/32360

(5) https://www.srilankabusiness.com/footwear-and-leather/footwear-and-leather-products-export-performance.html

(6) https://www.srilankabusiness.com/footwear-and-leather/overview.html

(7) http://www.ft.lk/business/550-m-footwear-and-leather-sector-thanks-Industry-Minister/34-671872?fbclid=IwAR1TITRiQ-TAB- aicjI5SBguj6whRvBYb9QFg WW5 mhkg-z5xH9syhKqtZP4

(The writer is the Chief Operating Officer of Advocata Institute. He can be contacted at dhananath@advocata.org. Learn more about Advocata’s work at www.advocata.org. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, or anyone affiliated with the institute)

Ban on slaughtering cattle

Adding to the banning spree, the proposed ban on slaughtering cattle is the latest. This may cause more damage rather than being helpful for the protection of cattle in Sri Lanka. However, the Cabinet Spokesperson mentioned the proposal was postponed by one month so as to allow for discussions with the relevant stakeholders.

Though the proposal may have been put forward with good intentions in terms of animal cruelty, India is a good example of how such policies don’t work. Cattle owners in India are left with no option other than to resort to the creation of illegal and unsanitary slaughtering houses and illegal markets.

Keeping aside the logical fallacy of placing a ban only on the slaughter of cattle and not the entirety of the poultry and meat industry, and the justification of leaving domestic demand to only be met through the importation of beef, the matter goes far beyond that.

The beef industry does not exist in isolation; our leather industry, dairy industry, and leather exports are also dependent on it. According to the Export Development Board (EDB), in 2016, about 1% of total merchandise exports (5) consisted of footwear and leather products, which has now dropped to 0.6% of our merchandise exports.

According to the EDB, there are about five large companies, 10 medium-scale companies, and more than 1,000 small enterprises and seven tanneries that produce 25 tonnes of leather every day (6).

If passed by Parliament, this proposed ban on cattle slaughter will prevail at the expense of 1,000 small enterprises and exports worth $ 550 million (7). While animal cruelty is of grave importance, sometimes in life we have to keep some markets for the greater good and to avoid much greater negative impacts.

References:

(1) http://www.colombopage.com/archive_17B/Sep01_1504285020CH.php

(2) http://www.adaderana.lk/news/55586/i-will-ban-carpentry-sheds-sawmill-owners-have-5-years-to-find-another-job-president

(3) http://www.ft.lk/columns/Economic-terrorism-by-COVID-19/4-705859

(4) https://mawbima.lk/news search/%20%E0%B6%BB%E0%B6%A2%E0%B6%BA%E0%B7%9A%20%E0%B6%BB%E0%B7%9D%E0%B7%84%E0%B6%BD%E0%B7%8A%20/print-more/32360

(5) https://www.srilankabusiness.com/footwear-and-leather/footwear-and-leather-products-export-performance.html

(6) https://www.srilankabusiness.com/footwear-and-leather/overview.html

(7) http://www.ft.lk/business/550-m-footwear-and-leather-sector-thanks-Industry-Minister/34-671872?fbclid=IwAR1TITRiQ-TAB- aicjI5SBguj6whRvBYb9QFg WW5 mhkg-z5xH9syhKqtZP4

(The writer is the Chief Operating Officer of Advocata Institute. He can be contacted at dhananath@advocata.org. Learn more about Advocata’s work at www.advocata.org. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, or anyone affiliated with the institute)

A common belief is that the “banning strategy” often fails or is less effective due to poor implementation. This is far from the truth. There is very much a market and an economic dimension that show the concept in itself is flawed, which we often fail to understand.

Emotional policymakers often get the art of public policy drastically wrong. They view it through an accounting lens due to a lack of knowledge on human behavioural economics and the presence of the concept called “markets”. As a result, all good intentions result in far worse consequences.

Ban on sachets

The concept of sachets was introduced by FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) market players on the basis of affordability and as a measure of resource allocation. Someone who cannot afford a full bottle of shampoo or any other equivalent product can use a sachet as a one-time useable product, based on the requirement. This is easy on customers’ wallets and provides value for money.

A good reason why sachets are predominantly available in general trade and mom-and-pop shops as opposed to modern trade is its easy access and affordability for the poor. On the other hand, from the manufacturer’s end, sachets help to allocate raw materials effectively and allow them to reach the market.

According to a recent article by Dr. Rohantha Athukorala (3), a Neilson Survey revealed that people have reduced the usage of baby soap by 18% and adult soap consumption by 17%. This indicates how people who find it difficult to manage their finances resort to eliminating basic hygiene products like adult and baby soap due to unaffordability. Cutting down on baby soap indicates a booming cost of living problem which goes beyond soap usage.

The ban on sachets will be a double whammy for most vulnerable people in society who are voiceless. All FMCG companies spend an enormous amount of money before they launch any SKU (stock-keeping unit), and we need to understand this was a market demand.

A common belief is that the “banning strategy” often fails or is less effective due to poor implementation. This is far from the truth. There is very much a market and an economic dimension that show the concept in itself is flawed, which we often fail to understand.

Emotional policymakers often get the art of public policy drastically wrong. They view it through an accounting lens due to a lack of knowledge on human behavioural economics and the presence of the concept called “markets”. As a result, all good intentions result in far worse consequences.

Ban on sachets

The concept of sachets was introduced by FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) market players on the basis of affordability and as a measure of resource allocation. Someone who cannot afford a full bottle of shampoo or any other equivalent product can use a sachet as a one-time useable product, based on the requirement. This is easy on customers’ wallets and provides value for money.

A good reason why sachets are predominantly available in general trade and mom-and-pop shops as opposed to modern trade is its easy access and affordability for the poor. On the other hand, from the manufacturer’s end, sachets help to allocate raw materials effectively and allow them to reach the market.

According to a recent article by Dr. Rohantha Athukorala (3), a Neilson Survey revealed that people have reduced the usage of baby soap by 18% and adult soap consumption by 17%. This indicates how people who find it difficult to manage their finances resort to eliminating basic hygiene products like adult and baby soap due to unaffordability. Cutting down on baby soap indicates a booming cost of living problem which goes beyond soap usage.

The ban on sachets will be a double whammy for most vulnerable people in society who are voiceless. All FMCG companies spend an enormous amount of money before they launch any SKU (stock-keeping unit), and we need to understand this was a market demand.

A sudden decision without prior engagement with the industry and relevant stakeholders will push manufactures to an extremely difficult situation, which will demand them to realign their manufacturing and marketing strategies in an already challenged Covid-19 economic environment. We have often forgotten that polythene is a wonderful innovation, and where its hydrocarbons are recycled to produce electronic chips and fabric.

MAS Holdings manufactured a special fabric for our cricket World Cup team with marine plastic waste which received global recognition. This can be utilised as an effective example to understand that the prime need is for setting up proper recycling methods coupled with incentives and disincentives.

Already, the discussion is heated on serious environmental concerns such as that of the Anawilundawa Wetland Sanctuary and many other places across the island, as highlighted through this column last week. The Government has to keep an eye on more macro issues pertaining to environmental protection rather than obsessively focusing on micro issues. These “banning strategies” will dilute the Government’s well-earned political capital, which will make hard reforms difficult in the coming years.

Import controls

Import controls are another form of ban on a temporary basis. The Government’s urgent need to manage its Balance of Payment (BoP) crisis is understandable. However, this requires a series of different actions coupled with temporary solutions such as bailout programmes from the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and clear policy decisions to help make our exports competitive.

Import controls hurt exports as the prices of import substitutes rise, especially where the goods are used as an input for the production of exports. In addition, import substitutes become more profitable to produce than exports.

The result of the current import ban is highly likely to affect our existing exports, as we have indicated in this column multiple times. Already, people are struggling to buy phone chargers, repair washing machines, and purchase goods which are required on a daily basis. We are running on existing stocks which will expire soon and prices have already started going up.

On the other hand, in our import bill, the big-ticket item is fuel and essentials such as pharmaceuticals, which are very difficult to control. The General Hospital has already announced a shortage of 70 essential drugs. These drugs are used to treat diseases such as Thalassemia and heart-related conditions (4).

However, trying to cut corners of other imports carry the potential to distort various other markets, businesses, and value chains horizontally, vertically, upstream, and downstream due to price hikes.

Prices of vehicle tyres and spare parts have shot up, which will have an impact on all goods and services with a transportation cost component. At one point, the collective effect of the rising cost of multiple consumable goods and intermediary goods may go beyond people’s affordability.

Releasing import controls at this point would be too late, given the situation of our currency. The higher cost of living will impact labour prices and most of our value addition in exports which are in the form of labour will be uncompetitive over a period, which will affect our main exports such as apparels, tea, and rubber products. In economics, the need is to take a look at the market from a holistic perspective. Otherwise, similar issues will arise over and over again.

The best example is higher prices requested by the poultry industry and the bakery industry. Sri Lanka’s maize production is not at all sufficient for domestic consumption, which is the main source of food for poultry. As a result of higher prices of maize, the prices of poultry products have shot up, which will have an impact on the bakery industry. Now you have a happy maize farmer but an unhappy poultry farmer and a baker. Eventually, this will translate to an unhappy consumer and a very unhappy voter.

A sudden decision without prior engagement with the industry and relevant stakeholders will push manufactures to an extremely difficult situation, which will demand them to realign their manufacturing and marketing strategies in an already challenged Covid-19 economic environment. We have often forgotten that polythene is a wonderful innovation, and where its hydrocarbons are recycled to produce electronic chips and fabric.

MAS Holdings manufactured a special fabric for our cricket World Cup team with marine plastic waste which received global recognition. This can be utilised as an effective example to understand that the prime need is for setting up proper recycling methods coupled with incentives and disincentives.

Already, the discussion is heated on serious environmental concerns such as that of the Anawilundawa Wetland Sanctuary and many other places across the island, as highlighted through this column last week. The Government has to keep an eye on more macro issues pertaining to environmental protection rather than obsessively focusing on micro issues. These “banning strategies” will dilute the Government’s well-earned political capital, which will make hard reforms difficult in the coming years.

Import controls

Import controls are another form of ban on a temporary basis. The Government’s urgent need to manage its Balance of Payment (BoP) crisis is understandable. However, this requires a series of different actions coupled with temporary solutions such as bailout programmes from the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and clear policy decisions to help make our exports competitive.

Import controls hurt exports as the prices of import substitutes rise, especially where the goods are used as an input for the production of exports. In addition, import substitutes become more profitable to produce than exports.

The result of the current import ban is highly likely to affect our existing exports, as we have indicated in this column multiple times. Already, people are struggling to buy phone chargers, repair washing machines, and purchase goods which are required on a daily basis. We are running on existing stocks which will expire soon and prices have already started going up.

On the other hand, in our import bill, the big-ticket item is fuel and essentials such as pharmaceuticals, which are very difficult to control. The General Hospital has already announced a shortage of 70 essential drugs. These drugs are used to treat diseases such as Thalassemia and heart-related conditions (4).

However, trying to cut corners of other imports carry the potential to distort various other markets, businesses, and value chains horizontally, vertically, upstream, and downstream due to price hikes.

Prices of vehicle tyres and spare parts have shot up, which will have an impact on all goods and services with a transportation cost component. At one point, the collective effect of the rising cost of multiple consumable goods and intermediary goods may go beyond people’s affordability.

Releasing import controls at this point would be too late, given the situation of our currency. The higher cost of living will impact labour prices and most of our value addition in exports which are in the form of labour will be uncompetitive over a period, which will affect our main exports such as apparels, tea, and rubber products. In economics, the need is to take a look at the market from a holistic perspective. Otherwise, similar issues will arise over and over again.

The best example is higher prices requested by the poultry industry and the bakery industry. Sri Lanka’s maize production is not at all sufficient for domestic consumption, which is the main source of food for poultry. As a result of higher prices of maize, the prices of poultry products have shot up, which will have an impact on the bakery industry. Now you have a happy maize farmer but an unhappy poultry farmer and a baker. Eventually, this will translate to an unhappy consumer and a very unhappy voter.

Ban on slaughtering cattle

Adding to the banning spree, the proposed ban on slaughtering cattle is the latest. This may cause more damage rather than being helpful for the protection of cattle in Sri Lanka. However, the Cabinet Spokesperson mentioned the proposal was postponed by one month so as to allow for discussions with the relevant stakeholders.

Though the proposal may have been put forward with good intentions in terms of animal cruelty, India is a good example of how such policies don’t work. Cattle owners in India are left with no option other than to resort to the creation of illegal and unsanitary slaughtering houses and illegal markets.

Keeping aside the logical fallacy of placing a ban only on the slaughter of cattle and not the entirety of the poultry and meat industry, and the justification of leaving domestic demand to only be met through the importation of beef, the matter goes far beyond that.

The beef industry does not exist in isolation; our leather industry, dairy industry, and leather exports are also dependent on it. According to the Export Development Board (EDB), in 2016, about 1% of total merchandise exports (5) consisted of footwear and leather products, which has now dropped to 0.6% of our merchandise exports.

According to the EDB, there are about five large companies, 10 medium-scale companies, and more than 1,000 small enterprises and seven tanneries that produce 25 tonnes of leather every day (6).

If passed by Parliament, this proposed ban on cattle slaughter will prevail at the expense of 1,000 small enterprises and exports worth $ 550 million (7). While animal cruelty is of grave importance, sometimes in life we have to keep some markets for the greater good and to avoid much greater negative impacts.

References:

(1) http://www.colombopage.com/archive_17B/Sep01_1504285020CH.php

(2) http://www.adaderana.lk/news/55586/i-will-ban-carpentry-sheds-sawmill-owners-have-5-years-to-find-another-job-president

(3) http://www.ft.lk/columns/Economic-terrorism-by-COVID-19/4-705859

(4) https://mawbima.lk/news search/%20%E0%B6%BB%E0%B6%A2%E0%B6%BA%E0%B7%9A%20%E0%B6%BB%E0%B7%9D%E0%B7%84%E0%B6%BD%E0%B7%8A%20/print-more/32360

(5) https://www.srilankabusiness.com/footwear-and-leather/footwear-and-leather-products-export-performance.html

(6) https://www.srilankabusiness.com/footwear-and-leather/overview.html

(7) http://www.ft.lk/business/550-m-footwear-and-leather-sector-thanks-Industry-Minister/34-671872?fbclid=IwAR1TITRiQ-TAB- aicjI5SBguj6whRvBYb9QFg WW5 mhkg-z5xH9syhKqtZP4

(The writer is the Chief Operating Officer of Advocata Institute. He can be contacted at dhananath@advocata.org. Learn more about Advocata’s work at www.advocata.org. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, or anyone affiliated with the institute)

Ban on slaughtering cattle

Adding to the banning spree, the proposed ban on slaughtering cattle is the latest. This may cause more damage rather than being helpful for the protection of cattle in Sri Lanka. However, the Cabinet Spokesperson mentioned the proposal was postponed by one month so as to allow for discussions with the relevant stakeholders.

Though the proposal may have been put forward with good intentions in terms of animal cruelty, India is a good example of how such policies don’t work. Cattle owners in India are left with no option other than to resort to the creation of illegal and unsanitary slaughtering houses and illegal markets.

Keeping aside the logical fallacy of placing a ban only on the slaughter of cattle and not the entirety of the poultry and meat industry, and the justification of leaving domestic demand to only be met through the importation of beef, the matter goes far beyond that.

The beef industry does not exist in isolation; our leather industry, dairy industry, and leather exports are also dependent on it. According to the Export Development Board (EDB), in 2016, about 1% of total merchandise exports (5) consisted of footwear and leather products, which has now dropped to 0.6% of our merchandise exports.

According to the EDB, there are about five large companies, 10 medium-scale companies, and more than 1,000 small enterprises and seven tanneries that produce 25 tonnes of leather every day (6).

If passed by Parliament, this proposed ban on cattle slaughter will prevail at the expense of 1,000 small enterprises and exports worth $ 550 million (7). While animal cruelty is of grave importance, sometimes in life we have to keep some markets for the greater good and to avoid much greater negative impacts.

References:

(1) http://www.colombopage.com/archive_17B/Sep01_1504285020CH.php

(2) http://www.adaderana.lk/news/55586/i-will-ban-carpentry-sheds-sawmill-owners-have-5-years-to-find-another-job-president

(3) http://www.ft.lk/columns/Economic-terrorism-by-COVID-19/4-705859

(4) https://mawbima.lk/news search/%20%E0%B6%BB%E0%B6%A2%E0%B6%BA%E0%B7%9A%20%E0%B6%BB%E0%B7%9D%E0%B7%84%E0%B6%BD%E0%B7%8A%20/print-more/32360

(5) https://www.srilankabusiness.com/footwear-and-leather/footwear-and-leather-products-export-performance.html

(6) https://www.srilankabusiness.com/footwear-and-leather/overview.html

(7) http://www.ft.lk/business/550-m-footwear-and-leather-sector-thanks-Industry-Minister/34-671872?fbclid=IwAR1TITRiQ-TAB- aicjI5SBguj6whRvBYb9QFg WW5 mhkg-z5xH9syhKqtZP4

(The writer is the Chief Operating Officer of Advocata Institute. He can be contacted at dhananath@advocata.org. Learn more about Advocata’s work at www.advocata.org. The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute, or anyone affiliated with the institute)